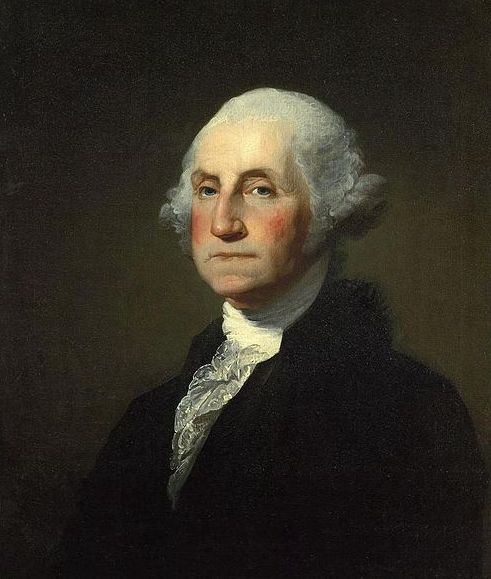

George Washington landed at Newport early on August 17, 1790. U.S. Congressman William Loughton Smith of South Carolina, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Blair of Virginia, Governor George Clinton of New York, and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson accompanied him.

The Touro Synagogue website provides the following account of this momentous visit; more can be found here: http://www.tourosynagogue.org/history-learning/gw-letter

Washington comes to Newport, Rhode Island

George Washington landed in Newport, Rhode Island, early on August 17, 1790. U.S. Congressman William Loughton Smith of South Carolina, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Blair of Virginia, Governor George Clinton of New York, and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson accompanied him.

In order to learn more about the country’s landscape, agricultural development, and the attitudes and dispositions of its citizens toward the new administration, the president had traveled to the New England states the previous fall. He purposefully avoided Rhode Island, which at the time had declined to hold a state convention to ratify the federal Constitution. Only until Rhode Island approved the Constitution in May 1790 did he decide to visit the state in public. In addition to highlighting the affection Rhode Islanders had for him as the Revolutionary hero, such a unique visit would elevate his reputation among the state’s officials.2.

Jefferson, Washington, and the others also had another goal in mind. The Congress had suggested twelve constitutional amendments. Press and religious freedom were addressed in the third amendment. On September 25, 1789, Congress passed all twelve amendments and sent them to the states for ratification. It was necessary for state legislatures to examine and ratify each amendment separately. The state legislatures returned the modifications to Congress over several months, approving some and rejecting others. Ten of the twelve proposed amendments were adopted by Virginia on December 15, 1791, making it the tenth and final state to do so before the additions became law. Three-quarters of all states had rejected the first two proposed changes, making them unsuitable for adoption. As a result, the newly ratified First Amendment replaced the original Third Amendment, which forbade the creation of a state religion and freedom of the press. When the President traveled to Newport in August 1790, the states of Virginia, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Georgia were still arguing about the additions.

Citizens of Newport address their new President:

A government has been established by the Majesty of the People.

Leading Newport residents and representatives of the city’s numerous religious groups, including the Jews, welcomed Washington and his delegation. Some of Newport’s slaves would have been among the crowd who welcomed Washington, as during the colonial era, people of African descent made up between 25% and 33% of Newport’s population. Letters welcoming the President were read by politicians, businesspeople, and religious leaders. Moses Seixas, a representative of Yeshuat Israel, Newport’s first Jewish congregation, was one of them. Seixas’s speech was a sophisticated way for the Jewish community to demonstrate their pride in Washington’s leadership and in a democracy. Seixas penned:

Having been denied the priceless rights of free citizenship up until this point, we now (with great thanks to the Almighty, who decides everything) see a government established by the Majesty of the People that generously grants everyone the freedom of conscience and the immunities of citizenship, deeming everyone, regardless of nationality, language, or language, to be equal parts of the vast governmental apparatus.4.

The President thanked the citizen organizations that had addressed him at Newport for their hospitality and civility in a letter he wrote a few days after departing. His letter to the Jews was the first of them. The letter represented the new government’s approach toward people whose religious beliefs were viewed as unusual, and it went beyond ordinary civility. Washington confirmed the views in the Seixas letter by echoing Seixas’ statement that “to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” Additionally, the President’s remarks aided in defining the federal government’s position in concerns of conscience.

Religion and Ratification

One major topic of contention in the ratification debate was the government’s involvement in religious matters. In England and throughout Europe, state-sponsored religion was commonplace. There may be dire repercussions if one’s beliefs diverged from those of the official Church. Although the first republics did not have an official religion, their colonial charters sometimes failed to distinguish between religion and governance. It was acknowledged that a just government was founded on Christian values and that non-Christians should be accepted for who they were, usually in the hopes that Jews, Turks, and unbelievers would convert to Christianity. Some states imposed taxes on their residents to fund religious institutions, while others limited the rights of minority groups including Quakers, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Catholics. Non-Christians were denied full citizenship rights, including the ability to run for public office, in the majority of states. Although they were shielded from overt prejudice by their role as merchants and economic contributors, Jews were nonetheless denied the right to vote and naturalization, even in religiously liberal Rhode Island.

These inequities were not significantly alleviated by the First Amendment’s provision that states that Congress may not enact laws that restrict the free exercise of religion or that create it. Its goals were to ensure the unalienable right to the free exercise of religion, at least at the federal level of government, and to stop the government from establishing an official state religion.

But Washington needed the support of both politicians and religious leaders to get this and the other amendments approved by the necessary majority of the states. Religious institutions, especially those that had faced prejudice in this country, congratulated Washington in numerous letters after his inauguration in April 1789, each applauding his leadership in the struggle to uphold religious liberty in the new republic. In response to these letters, Washington made it apparent that he wanted religious freedom to be enshrined in national law. In March 1790, he wrote to the Roman Catholics, Methodists, Congregational clergy, the General Assembly of Presbyterian congregations, and the United Baptist churches in Virginia. Each letter emphasized the idea of religious freedom and, similar to his speech at the Quaker annual meeting, promised that the new nation would uphold everyone’s freedom to worship their own god and their own conscience.

Jewish congregations in America were similarly excited to embrace the new president. Following a suggestion made by Manuel Josephson of Mikve Israel in Philadelphia, the leaders of Shearith Israel in New York sent a letter to the Hebrew congregations in Newport, Philadelphia, Richmond, and Charleston in June 1790, requesting that they unite in writing to Washington. The speech delivered to President Washington in May 1790 by the Mikveh Israel congregation of Savannah, Georgia, acting alone, appears to have served as a catalyst for this endeavor. On July 2, 1790, Moses Seixas responded on behalf of the Hebrew congregation in Newport, stating that although his congregation supported the idea of a joint speech, they were hesitant to offend the state legislature by speaking to the president before that body had done so. As a result, his congregation did not speak to him directly until the President came to Newport in August 1790. A combined letter composed by the remaining congregations in Charleston, Philadelphia, Richmond, and New York was not sent until December 1790.

On August 21, 1790, Washington wrote a Letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, in response to the Newport group’s address. The President expressly recognizes Jewish involvement in the new country, as he has done in previous letters to Jewish congregations. The Newport letter, however, is notable for its unambiguous and straightforward wording. May the descendants of Abraham who inhabit this land continue to earn and benefit from the goodwill of their fellow citizens, Washington says. Echoing the Declaration of Independence, he continues by opposing the bare toleration of religious differences and emphasizing religious liberty in the enjoyment of inherent natural rights.

Melvin Urofsky, an American historian, has penned:

Although this letter carries with it a unique and cherished significance for American Jewry, in many ways it is a treasure of the entire nation. America, as de Tocqueville [a French political thinker and historian who visited America in the early 1800s] famously wrote, had been born free, unfettered by the religious and social bigotries of medieval Europe. The United States, although initially founded by people from the British Isles, had well before the Revolution become a haven of many peoples from continental Europe seeking political and religious freedom and economic opportunity. The new nation recognized this diversity for what it was, one of the country s greatest assets, and took as its motto E Pluribus Unum Out of Many, One . The separation of church and state, and with it the freedom of religion enshrined in the First Amendment to the Constitution, has made the United States a beacon of hope to oppressed peoples everywhere.5.

Washington s commitment to religious liberty, the involvement of all people in the new democracy and the campaign for passage of the Bill of Rights combined on that August day in Newport, Rhode Island. The result is the Letter to the Hebrew Congregations of Newport, a profound statement of the values that make America an example to the world.

Gentlemen:

While I received with much satisfaction your address replete with expressions of esteem, I rejoice in the opportunity of assuring you that I shall always retain grateful remembrance of the cordial welcome I experienced on my visit to Newport from all classes of citizens.

The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security.

If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good government, to become a great and happy people.

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my administration and fervent wishes for my felicity.

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.

May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.

G. Washington

Sources:

2The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition, ed. Theodore J. Crackel.Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2007. Accessed (24 Nov 2007) inhttp://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/pgwde/search-Pre06d132

3Moses Seixas on behalf of Congregation Yeshuat Israel, to George Washington, 17 August 1780, in Dorothy Twohig, et. al., eds.The Papers of George Washington: Presidential Series. University Press of Virginia, 1986, 6:286n.1.

4Newport Jewry and The Touro Synagogue. Melvin Urofsky, unpublished Manuscript, 2003, p.98.

More from What’sUpNewp

Morning Notes: Easton s Beach remains closed for third day due to bacteria

Mount Hope Bridge reopens ahead of schedule after resurfacing

Obituary: Carole Anderson

Trevor Story hits a 3-run homer as the Red Sox hold off the Marlins for a 7-5 win

Something went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.